Lead, arsenic and cadmium are commonly found in baby foods, but also in many of the ingredients families use to make their own.

When Congress released a report this month finding that popular baby foods contain worrisome levels of toxic heavy metals, the reaction was swift.

Scary headlines blared from the New York Times to the Daily Mail, lawsuits were filed within days and throngs of parents, already beleaguered from the stresses of the pandemic, took to social media with the fire of a thousand suns. “You knowingly sell food that hurt babies for profit,” one mom wrote on a baby food company’s Instagram page. “You are MONSTERS.”

But the intense blowback against baby food makers obscured an even larger problem, watchdogs say: Heavy metal contamination is relatively common across the food supply, so infants aren’t the only children vulnerable to possible health effects, and the federal government is doing next to nothing to reduce their exposure.

The Food and Drug Administration has yet to take any action, despite having spent three years quietly exploring the issue of toxic contaminants in food during the Trump administration.

“This is not a baby food problem. This is a food problem,” said Tom Neltner, chemicals policy director at the Environmental Defense Fund, which has lobbied for more regulation of heavy metals.

The congressional report, released earlier this month by a House Oversight Committee panel, found that four major baby food brands — Beech-Nut, Gerber, Earth’s Best Organic and HappyBABY — sold products that their own internal testing showed contained arsenic, lead and cadmium at levels far higher than what most health experts consider safe for infants.

In the days following the report, each of the baby food companies sought to reassure parents that their products are safe and that they follow very high standards for sourcing ingredients, but it’s done little to lessen the blowback.

Though in some cases the companies knew their ingredients contained elevated levels of heavy metals, the baby food makers at the center of the investigation weren’t violating any rules because the FDA has not set standards for most heavy metals in baby food.

The FDA, which has historically focused most of its attention on foodborne pathogens like Salmonella and Listeria, in 2017 launched a working group to look at heavy metals and other contaminants in food, cosmetics and supplementsto little fanfare — a move that was partly a reaction to an EPA study from earlier that year that found food was a surprisingly significant source of lead exposure for young children.

A chart that was buried in supplementary material in the study showed that about half of blood lead exposure formost children between the ages of 1 and 6 comes from food. The next biggest contributors: soil and dust (including from lead-based paint), air and water.

Significant problem

It’s an important revelation because lead exposure remains a significant public health problem in the United States. One study estimated that preventing all lead exposure in just the babies born in the year 2018, for example, would deliver $80 billion in societal benefits, in large part due to the increased earnings potential of children with higher IQs and fewer behavioral and health problems.

About two million children, or nearly 10 percent of all young kids, are estimated to consume more lead than the FDA’s current limiteach day, according to the government’s own estimates.

Lead is among the best-known and best-studied neurotoxins, but arsenic, cadmium, and mercury are also routinely found in foods at low levels. As scientists have begun to better understand the health risks from long-term, low-level exposure, and labs have grown better at detecting contaminants at very low levels, more attention has turned to the food supply.

The issue has been on the FDA’s radar, but there have been no changes to any food standards.

Now, with the fresh public outrage over baby food, the Biden administration faces pressure to act, even as it is still without a nominee for FDA commissioner.

The agency, in a statement to POLITICO, said it is reviewing the congressional subcommittee’s baby foodreport.

“The FDA takes exposure to toxic elements in the food supply extremely seriously, especially when it comes to protecting the health and safety of the youngest and most vulnerable in the population,” an FDA spokesperson said in an email, noting that heavy metals are found throughout the environment. “Because they cannot be completely removed, our goal is to reduce exposure to toxic elements in foods to the greatest extent feasible and we have been actively working on this issue using a risk-based approach to prioritize and target the agency’s efforts.”

The FDA did not respond to the criticism that it’s been slow to act on the issue, but did acknowledge “that there is more work to be done.”

The reality is that concerning levels of lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium can routinely be found in many foods, including rice, sweet potatoes, carrots, juices and spices. The contamination is happening throughout the food supply — not just in baby food — which means that parents cannot avoid heavy metals simply by making their own food.

Crops pull up heavy metals from soil, where some of the metals are naturally occurring but much of the contamination stems from more than a century of pollution, from car exhaust to coal emissions and agricultural chemicals.

Emissions spread heavy metal particles through the air where they eventually settle into soil and water. In the early 20th century, it was common for farmers to use pesticides made with lead and arsenic, especially to grow cotton in the south. Heavy metals don’t degrade, which means crops grown decades later can absorb old contaminants through their roots.

“Parents can’t solve this problem by shopping in the produce aisle and not the baby food aisle,” said Jane Houlihan, research director at Healthy Babies Bright Futures, a nonprofit focused on reducing babies’ exposure to toxic chemicals. “FDA has to take action.”

Small amounts

The good news is that the general population’s exposure to heavy metals has been going down over time, particularly after the government started phasing out leaded gasoline, paints and food cans in the 1970s, which led to a steep drop off in blood levels of lead in children. The bad news is that scientists have only recently come to better understand just how damaging heavy metals can be, particularly for babies and young children, even at very, very low levels.

Even exceedingly small amounts of these neurotoxins can impede a child’s IQ, hinder brain development, lead to behavioral problems, increase cancer risk, and raise the chances of many other diseases. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, maintains there’s no known safe blood level of lead in children.

“What’s come into clearer view is that this is an urgent public health problem,” Houlihan said.

Right now, parents and other caretakers are essentially at the mercy of whatever standards baby food companies decide to set for themselves — and the extent to which they actually conduct their own tests and hold themselves to those internal standards.

Exactly how low the limit should be for heavy metals in baby food is a matter of debate, but public health advocates contend it should be as low as possible — and there is broad agreement that the few standards FDA currently has are not strict enough to protect babies and young children.

Back in 2013, FDA proposed a voluntary limit for inorganic arsenic in apple juice at 10 parts per billion and the agency has still not finalized the guidance more than seven years later.

Consumer Reports has since pushed for a limit of 3 ppb for all juices, arguing that the agency’s initial guidance — which companies tend to take seriously — was a step in the right direction, but didn’t do enough to mitigate the risk of developmental problems posed by arsenic exposure.

In 2016, the FDA,responding to outside pressure from Consumer Reports and others, set a voluntary limit for inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal at 100 ppb, but the agency set this level based on cancer risks and what was feasible for the industry at the time, not neurological development risks, which have been shown at much lower levels. Public health advocates have urged the agency to lower this limit.

The agency has also been criticized for lax oversight. Independent tests have shown infant rice cereal makers sometimes sell products that exceed the standard with no repercussions.

Developmental harm

There are no federal standards for lead in baby food, but the FDA has set a 5 ppb lead standard for bottled water, 50 ppb for juice and 100 ppb for candy. By comparison, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a 1 ppb limit for school drinking fountains — a threshold that consumer advocates would like to see applied to juice, too.

Cadmium has received far less attention compared to other toxic metals like arsenic and lead, but it’s also prevalent in the food supply. FDA has no standards on cadmium in any foods. Consumer Reports has urged the agency to set a limit of 1 ppb for cadmium in fruit juice.

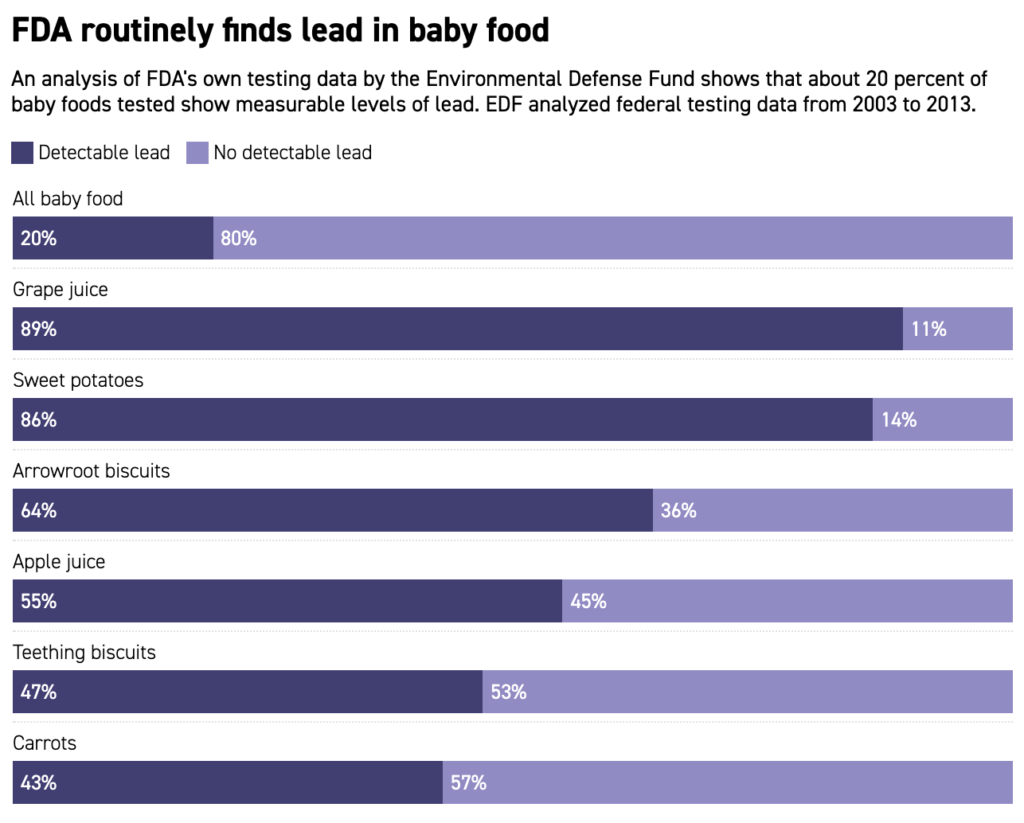

But heavy metals have prompted the greatest concern by far when found in baby foodbecause infants and young children are the most vulnerable to developmental harm. In 2017, the Environmental Defense Fund analyzed FDA’s own routine testing of the food supply and found there were measurable lead levels in 20 percent of baby products tested.

The same year, a Colorado-based nonprofit called the Clean Label Project tested some 500 of the country’s best-selling baby foods — one the largest samples to date — and found that nearly 40 percent contained at least trace levels of one heavy metal and 25 percent contained all four, though overall the levels were relatively low.

The following year, Consumer Reports tested 50 popular baby food products and found two thirds contained “worrisome levels” of at least one heavy metal. They reported that 15 of the products tested would pose health risks to children if regularly consumed. Products containing rice and sweet potatoes were particularly likely to test positive. Organic products were just as likely to be contaminated as conventional products.

The House Oversight subcommittee got the idea to look into baby food after another report in 2019 by Healthy Babies Bright Futures, a nonprofit, tested nearly 170 products and found heavy metals present in 95 percent of their samples. Most foods had relatively low levels, but there were product categories that showed higher levels, including lead in carrots and sweet potatoes and particularly arsenic in rice. Four of the seven infant rice cereals tested exceeded FDA’s voluntary limits for inorganic arsenic. The group is urging FDA to set standards for baby food, arguing that repeated exposure at very low levels adds up and poses health risks.

The congressional report this month was based on data that companies voluntarily turned over to the subcommittee. The report reveals that many of the ingredients and products that were tested by companies themselves contained heavy metals at levels that exceed even generous voluntary limits and even some companies’ own internal limits.

“Our worst fears were confirmed,” a senior Democratic committee aide told POLITICO.

It’s difficult to draw broad conclusions about the baby food supply from the report, since it’s not clear how often companies are testing or how much of their own data they turned over to the committee, but the data that were released show numerous examples of significant levels of heavy metals getting through the supply chain and onto store shelves.

For instance, HappyBABY, an organic baby food brand, sold products that tested positive for lead at levels as high as 641 ppb and arsenic as high as 180 ppb, nearly twice FDA’s limit for rice cereal. Nearly 20 percent of the company’s finished products contained over 10 ppb of lead, according to the committee.

In a statement to POLITICO, the company said the data presented in the report was based on “a small portion” of its portfolio and is “not representative generally of our entire range of products at-shelf today.”

“We are disappointed at the many inaccuracies, select data usage and tone bias in this report,” the company said in an email. “We can say with the utmost confidence that all Happy Family Organics products are safe for babies and toddlers to enjoy, and we are proud to have best-in-class testing protocols in our industry.”

Beech-Nut, which markets itself as a “real food” brand, used nearly 90 different ingredients that had tested positive for lead at more than 15 parts per billion, including cinnamon that had been shown to be as high as 886 parts per billion.

Beech-Nut Nutrition said the company is currently reviewing the congressional report and will continue to support setting “science-based standards that food suppliers can implement across our industry.”

“We want to reassure parents that Beech-Nut products are safe and nutritious,” the company said.

Industry standards

Most of the companies targeted by the subcommittee’s investigation, including Gerber and Hain Celestial, which makes Earth’s Best Organic, are part of a group called the Baby Food Council, a partnership with Cornell University and the Environmental Defense Fund to set industry standards for baby food. Three other leading companies didn’t turn over testing data to the committee.

Nonetheless, the findings of the congressional report sparked concern bordering on panic by many parents and other caretakers, especially a year into a pandemic that’s upended schools, jobs, childcare and family support for millions of families.

Emily Oster, a popular economist and author on parenting issues, wrote that she was inundated with so many emails from parents that she moved her weekly newsletter up a few days to help answer questions. (She concluded that more rigorous government standards make sense and parents might consider cutting back on rice products, but should otherwise try not to worry about this too much.)

Moms flooded the social media pages of baby food brands with blistering anger. Some said they’d been in tears over the news, thinking they’d harmed their children. Several demanded to see testing results, threatened to sue, or said they were planning to take their children to the doctor to have their blood tested for heavy metals. Others said they were tossing out all their store bought food and boycotting the companies in the report.

“I have spent this last year home schooling and trying to figure [out] child care,” wrote one mom of three to Beech-Nut on the company’s Instagram page, who said her youngest had been born right at the start of the pandemic. “I have been worried sick that family would get sick. Now I learn I have something completely new to worry about.”

Every expert POLITICO interviewed for this story said it was unfortunate that parents might think they need to avoid all pre-made foods, particularly at such a stressful time.

The fact is that making baby food from scratch would probably not meaningfully reduce a child’s exposure to heavy metals. Digging deeper into the congressional report, it’s clear that many common ingredients can be contaminated and a caretaker has no way of knowing whether the sweet potatoes, kale and cinnamon in their own kitchen are any less contaminated than what baby food companies are sourcing.

The more fundamental issue, advocates say, is that there aren’t standards in place to pressure the supply chain to reduce exposure as much as possible.

“FDA has failed. They failed to set standards for baby food that companies have to meet. And they’ve failed to help, busy, sleep-deprived parents make better choices,” said Scott Faber, senior vice president of government affairs at the Environmental Working Group.

“The idea that new parents are going to navigate this is insane,” he added. “We’re not all nutritionists and toxicologists.”

The House subcommittee that sparked the firestorm earlier this month is planning to do more oversight on baby food, a senior Democratic committee aide told POLITICO. It makes sense to first focus on babies and small children because they are the most vulnerable to the developmental harm from heavy metals, the aide said.

“If you fail to address it here, there will be no broader action,”the aide said.

The subcommittee is working on a billthat would require FDA to come up with standards for heavy metals in baby foods and put in place testing requirements, among other things. Even if such a bill becomes law, it would likely take FDA several years to set such standards, if the agency’s past timelines are any indication.

“We don’t want to wait for that,” the committee aide said.

House Democrats are optimistic that the Biden administration will be open to working on this issue. One hopeful sign: Biden’s pick to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, which sits atop FDA, is Xavier Becerra, the former attorney of California who in 2018 sued two toddler milk companies over allegations they sold products with elevated levels of lead. Becerra’s office also recently went after seafood companies for selling products contaminated with lead and cadmium.

Becerra’s crackdown on seafood processors reflects a recognition that toxic-metal contamination affects more than just baby food.

Practical steps

While parents await action from the FDA, there are some practical steps they can take to protect their children from elevated levels of metal contaminants, health and consumer advocates say: Avoid or limit rice products for infants and young children. Oatmeal infant cereal or other grain cereals, for example, can contain far less arsenic. Brown rice tends to contain higher levels of arsenic than white rice.

Rice puff and teether snacks appear to sometimes test at concerningly high levels of arsenic. Until more is known, it may make sense to swap in other snacks to cut back on potential exposure.

Parents can also cut back on juice, since apple and grape juice commonly contain low levels of arsenic and lead, and instead choose water or milk. Certain vegetables like carrots and sweet potatoes, while healthy options overall, have been shown to contain more heavy metals than others, so serving a wide variety of vegetables is a good idea.

Pediatricians across the country, all of a sudden hounded by questions about heavy metal exposure, have tried to strike a balance for worried parents: Don’t panic. Focus on variety. The American Academy of Pediatrics released tips for parents, suggesting that they can also have their home water tested for heavy metals — in addition to making slight shifts in the diet — but ultimately: “Stronger rules and regulations for testing and limiting the amount of heavy metals in foods for babies and toddlers are most important.”

Phil Landrigan, a pediatrician and children’s health researcher at Boston College who played a crucial role in the government crackdown on lead decades ago, agrees that FDA action is urgently needed.

Ultimately, this is not a problem that should fall to caregivers to navigate, especially when low levels of these toxins have sweeping health consequences for future generations, he explained.

“Parents have done nothing wrong,” he said. “They’ve been hoodwinked by these companies and failed by their government.”

(Source: https://www.politico.com/news/agenda/2021/02/28/fda-toxic-metals-food-471757)